This guest post is by Theophile Loubiere.

# Solving a Sudoku with SBY and Formal Verification

Recently, I began using SBY to formally verify my designs. You can check out my first attempt on my blog learn-fpga-easily. Formal Verification helps ensure that certain properties of your design always remain true, such as:

- Bus arbitration: “Only one master can receive the bus grant at any given time.”

- Overflow and Underflow: “The FIFO buffer will never overflow or underflow.”

- State Machine Reachability: “The state machine can never transition from state_1 to state_3.”

These kinds of properties would normally require an extensive functional testbench for coverage. However, with formal verification and SBY, they can be easily addressed with just a few assertions and assumptions.

Given my newfound knowledge, it seemed completely natural that after embarrassingly failing to solve a Sudoku puzzle with my grandfather – a hit to my pride – I decided to repurpose the use of SBY just to figure out a Sudoku solution.

Today, I am excited to share with you my overkill attempt to solve a simple Sudoku puzzle with SBY and Formal Verification.

# Modeling the Sudoku

In Verilog, we can represent a Sudoku grid straightforwardly: a two-dimensional register encompassing 9 rows and 9 columns, where each cell occupies 4 bits:

module sudoku (

input clk,

);

// Internal 9x9 grid to make operations more intuitive

(* keep *) reg [3:0] sudoku_grid[8:0][8:0];

`ifdef FORMAL

// see next section

`endif

endmodule

Using the (* keep *) attribute ensures our register won’t be discarded during synthesis, even if it isn’t used anywhere.

And that’s it! Now, let’s dive into the interesting part: Formal Verification.

# How to solve a sudoku with Formal Verification ?

Formal verification involves setting specific properties that your design must always satisfy. The formal solver then evaluates a vast array of mathematically choosen scenarios. If a property doesn’t always hold true, the solver will tell you: “Nope, your property does not hold true in this counter-example.”

But here’s the catch: If we lay down just one property, the solver might churn out a completely irrelevant solution. Take Sudoku: Every row in a correctly solved grid has every digits from 1 to 9. One obvious property is the sum of digits in a row totaling 45 (because 1+2+3+…+9=45). Yet, with just this, the solver might suggest a row like: 0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,45. Clearly flawed, given illegal numbers and the repetition.

We must assume additional properties to narrow down the solution space and obtain relevant counterproofs:

- In digital design, we assume valid input behavior, focusing assertions on internal and output signals.

- For this Sudoku escapade, where we’re playfully repurposing the tool, assumptions will lean on the sudoku_grid register (typically a target for assertions).

So, what assumptions should we make for Sudoku? The basic rules.

# Assuming the Basic Rules

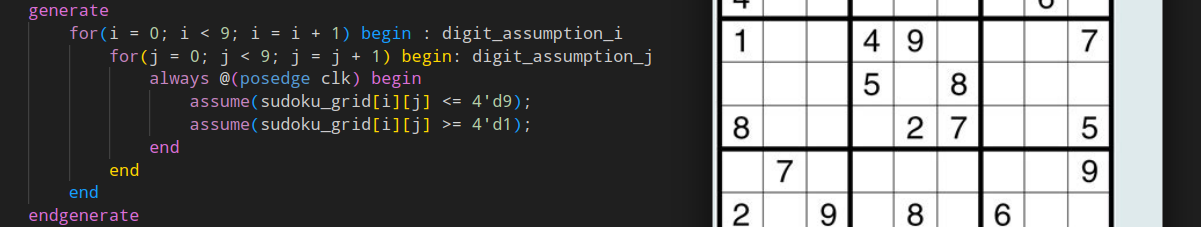

- All digits should be between 1 and 9. Which translates to:

`ifdef FORMAL

// variables declaration for all forloops

genvar box_row, box_col, i, j, k, m, n;

// assume all the digits are between 1 and 9

generate

for(i = 0; i < 9; i = i + 1) begin : digit_assumption_i

for(j = 0; j < 9; j = j + 1) begin: digit_assumption_j

always @(posedge clk) begin

assume(sudoku_grid[i][j] <= 4'd9);

assume(sudoku_grid[i][j] >= 4'd1);

end

end

end

endgenerate

With these assumptions, the solver won’t try any numbers that are outside of this range.

- All digits in a row are all different

generate

for(i = 0; i < 9; i = i + 1) begin: row_check

for(j = 0; j < 9; j = j + 1) begin: column_j

for(k = j + 1; k < 9; k = k + 1) begin: column_k

always @(posedge clk) begin

assume(sudoku_grid[i][j] !== sudoku_grid[i][k]);

end

end

end

end

endgenerate

- All digits in a column are all different

generate

for(i = 0; i < 9; i = i + 1) begin: column_check

for(j = 0; j < 9; j = j + 1) begin: row_j

for(k = j + 1; k < 9; k = k + 1) begin: row_k

always @(posedge clk) begin

assume(sudoku_grid[j][i] !== sudoku_grid[k][i]);

end

end

end

end

endgenerate

- All digits in a box are all different

generate

for(box_row = 0; box_row < 3; box_row = box_row + 1) begin: box_row_check

for(box_col = 0; box_col < 3; box_col = box_col + 1) begin: box_col_check

for(i = 0; i < 3; i = i + 1) begin: row_i_check

for(j = 0; j < 3; j = j + 1) begin: col_j_check

for(m = 0; m < 3; m = m + 1) begin: row_m_check

for(n = 0; n < 3; n = n + 1) begin: col_n_check

// Make sure we're not comparing the same cell to itself

if(i !== m || j !== n) begin

always @(posedge clk) begin

assume(sudoku_grid[(3*box_row)+i][(3*box_col)+j] !== sudoku_grid[(3*box_row)+m][(3*box_col)+n]);

end

end

end

end

end

end

end

end

endgenerate

- The initial grid cannot be changed.

// assume the intial grid

always @(posedge clk) begin : initialization

//line 1

assume(sudoku_grid[0][0]==5);

assume(sudoku_grid[0][2]==7);

assume(sudoku_grid[0][3]==2);

assume(sudoku_grid[0][7]==9);

//line 2

assume(sudoku_grid[1][2]==6);

assume(sudoku_grid[1][5]==3);

assume(sudoku_grid[1][6]==7);

assume(sudoku_grid[1][8]==1);

//line 3

assume(sudoku_grid[2][0]==4);

assume(sudoku_grid[2][7]==6);

//line 4

assume(sudoku_grid[3][0]==1);

assume(sudoku_grid[3][3]==4);

assume(sudoku_grid[3][4]==9);

assume(sudoku_grid[3][8]==7);

//line 5

assume(sudoku_grid[4][3]==5);

assume(sudoku_grid[4][5]==8);

//line 6

assume(sudoku_grid[5][0]==8);

assume(sudoku_grid[5][4]==2);

assume(sudoku_grid[5][5]==7);

assume(sudoku_grid[5][8]==5);

//line 7

assume(sudoku_grid[6][1]==7);

assume(sudoku_grid[6][8]==9);

//line 8

assume(sudoku_grid[7][0]==2);

assume(sudoku_grid[7][2]==9);

assume(sudoku_grid[7][4]==8);

assume(sudoku_grid[7][6]==6);

//line 9

assume(sudoku_grid[8][1]==4);

assume(sudoku_grid[8][5]==9);

assume(sudoku_grid[8][6]==3);

assume(sudoku_grid[8][8]==8);

end

# Using SBY to solve the Grid

With the game rules handed over to our solver, we want it to return the solution now.

As highlighted before, in a correctly solved Sudoku, every row, column, or box’s digit sum is 45. We simply need to request an example where this property holds true. And since there’s only one such example, it elegantly unfolds as our desired Sudoku solution.

// Ask SBY to explicitly cover the (only) case where sum=45s

wire [5:0] sum;

assign sum = sudoku_grid[0][0] +

sudoku_grid[0][1] +

sudoku_grid[0][2] +

sudoku_grid[0][3] +

sudoku_grid[0][4] +

sudoku_grid[0][5] +

sudoku_grid[0][6] +

sudoku_grid[0][7] +

sudoku_grid[0][8];

always @(*) begin

cover(sum==6'd45);

end

`endif FORMAL

endmodule

# Let’s run the verification

To install SBY and all the required formal solvers, I recommend following the straightforward installation process provided by oss-cad-suite.

To execute the verification, we’ll need our sudoku.v file and a SBY configuration file named sudoku.sby with the content below:

[options]

mode cover

[engines]

smtbmc

[script]

read -formal sudoku.v

prep -top sudoku

[files]

sudoku.v

All we have to do is run the following command :

sby -f sudoku.sby

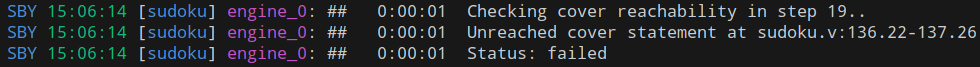

And as you can see… it fails… WAIT! WHAT?

SBY log

SBY log

“Unreached cover statement…” What does that mean?

- The line assumptions are correct.

- The row assumptions are correct.

- The box assumptions are correct.

- The… line 2 of the initialization is wrong…

assume(sudoku_grid[1][5]==3); // wrong

assume(sudoku_grid[1][4]==3); // correct

When I visited my grandfather, I handed him the original and copied it onto a paper to solve it myself… I made a copying error(deep breath)… At least we stumble upon a unexpected feature : we now know how to identify an unfeasible grid !

Now, after correcting my mistake, it works as expected: SBY generates the solution for me!

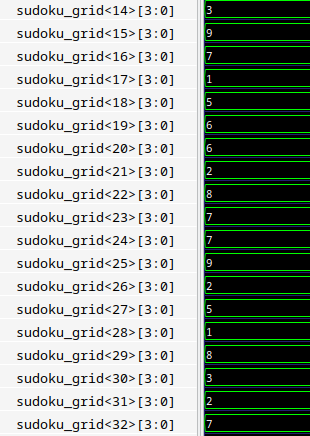

Here’s the solution viewed through gtkwave (SBY give you the path of the vcd file):

GTKWave screenshot

GTKWave screenshot

Hmm… that’s not very user-friendly to interpret.

Let’s take the futility of this exercise a step further and craft a Python script to visualize the solution. I’ve employed the pyDigitalWaveTools Python library to convert my VCD file into JSON format and have requested ChatGPT to create a script that reads the JSON and displays the solution in my terminal. All the sources can be accessed my github page.

Now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for - the solution:

5 1 7 | 2 6 4 | 8 9 3

9 2 6 | 8 3 5 | 7 4 1

4 8 3 | 9 7 1 | 5 6 2

---------------------

1 3 5 | 4 9 6 | 2 8 7

7 9 2 | 5 1 8 | 4 3 6

8 6 4 | 3 2 7 | 9 1 5

---------------------

3 7 8 | 6 4 2 | 1 5 9

2 5 9 | 1 8 3 | 6 7 4

6 4 1 | 7 5 9 | 3 2 8

# Conclusion

Let’s wrap this up. First off, if you’re ever stuck on that pesky Sudoku during a lazy Sunday afternoon, you now know there’s a… let’s call it an “alternative” way to crack it. And check it is actually feasible.

Now, on the real note: diving into techy stuff using simple problems we already know? It’s golden! It’s like trying to learn a new dance step with a song you already love. You get the hang of it faster and, more importantly, it’s fun. Playing around with SBY in this wild way just shows how cool and flexible these tools can be.

Big Thanks to YosysHQ for letting me write on their blog. And to you, dear reader, remember: mix things up, try the unexpected, and most importantly, have some fun while you’re at it. Till next time!