This is a guest blog post by Matt Young

# Foreword

Although I’m a computer scientist by education, I’ve always been interested in space since I was a kid. For a long time, I had simply forgotten about this interest, as I got more in-depth into FPGAs, then ASICs, and eventually EDA. I had no idea that eventually, an incredible opportunity would come to combine these two together, thanks to Yosys!

In late 2023, I pitched a research project to my academic supervisor at the University of Queensland in Australia. Here, we have a degree “Bachelor of Computer Science (Honours)” that is somewhat similar to a Master’s degree as it involves a one-year research thesis. At the time, I had simply pitched the design and implementation of a simple RISC-V microcontroller. As my supervisor pointed out, this is a fun project, but has little to no research potential.

As we brainstormed ways to improve the project, I recalled hearing about a Super Mario 64 speedrun that was allegedly disrupted by a random bit flip caused by a stray cosmic ray. As I did more serious research into this topic, I found a very interesting research field with all sorts of interesting trade-offs, on top of the ones you get in normal FPGA/ASIC design.

I quickly realised that far more than just designing one fault-tolerant processor, it could be possible to design a generalised EDA flow that could make any processor fault-tolerant.

Thankfully, I was already familiar with Yosys. In Australia, unlike Europe and the US, we do not currently have a very large or well-resourced domestic FPGA/ASIC research community. This means that, as university students and researchers, we don’t often (or ever) have access to industry tools like Cadence and Synopsys, so I had started my FPGA work using purely open-source tools. This, in fact, turns out to be a blessing in disguise. I’m passionate about FOSS tools, and Yosys - being open-source - allows you to peel back the hood and deeply understand how it does certain synthesis passes, which allows for really deep learning, plus the opportunity to improve the tool yourself. Very importantly, it also means that custom passes can easily be added, which is not at all possible with restrictive commercial tools. This makes it a very important tool in academia, and indeed, Yosys is coming up in more and more publications.

The project I ended up pitching, and had approved, was titled, “An Automated Triple Modular Redundancy EDA Flow for Yosys”.

# Background - What is Triple Modular Redundancy?

For safety-critical sectors such as aerospace, defence, and medicine, ASICs and FPGAs need to be designed to be fault tolerant to prevent catastrophic malfunctions. In the context of digital electronics, fault tolerant means that the design is able to gracefully recover and continue operating in the event of a fault, or upset.

For systems that operate in space - whether that be low-Earth orbit (LEO) or deep space - we care most about Single-Event Upsets (SEUs). SEUs are caused when ionising radiation strikes a transistor, causing it to transition from a 1 to a 0, or vice versa.

In space, the Earth’s atmosphere is absent, and thus chips are completely unprotected from the ever-present threat of radiation. This radiation can come from many sources: stray cosmic rays, violent bursts from the Sun, or even extremely powerful extragalactic gamma-ray bursts. On an unprotected system, an unlucky SEU may corrupt the system’s state to such a severe degree that it may cause destruction or loss of life - particularly important given the safety-critical nature of a number of space-faring systems (satellites, crew capsules, etc).

One way we can protect against SEUs is a design technique called Triple Modular Redundancy (TMR), which mitigates SEUs by triplicating key parts of the design and using voter circuits to select a non-corrupted result if an SEU occurs. Typically, TMR is manually designed by HDL designers, for example, by manually instantiating three copies of the target module, designing a voter circuit, and linking them all together. However, this approach is an additional time-consuming and potentially error-prone step in the already complex design pipeline.

Wouldn’t it be nice if, instead, we could just have our synthesis tool do this for us? You input a design, and

a simple tmr command makes it reliable enough to run in space, with barely any extra effort?

This may still be a pipe-dream, but was the goal of my thesis to explore.

# Introducing TaMaRa

TaMaRa is the name for my implementation of this as a pass in Yosys. Once compiled, it introduces one new

command: tamara_tmr, which aims to introduce TMR into the circuit. It also automatically calculates an err

signal that is set high when a fault occurs, which can be used to, for example, re-configure an FPGA or reboot

an ASIC.

Designers should only need to make one change to the design, which is to introduce the (* tamara_error_sink *)

annotation on the signal they would like to use as the error signal. This will indicate to the tool which port

should be wired up to the automatically generated error signal logic.

module my_module(

input a,

input b,

(* tamara_error_sink *)

input err

);

endmodule

If you are hoping to use TaMaRa on an existing project - there is some bad news. Unfortunately, we have very little time in Honours, and TaMaRa is absolutely not suitable for any real-world designs yet. In fact, it was only able to process a small number of simple test circuits and has a number of documented bugs on moderately complex designs. Think of it more as a proof of concept.

# TaMaRa - Under the hood

TaMaRa operates on Yosys’ powerful RTLIL or RTL Intermediate Language. All Yosys frontends emit this intermediate representation after pre-processing, lexing, parsing and elaboration. This is a very powerful feature of Yosys - it means that the same underlying plugin can operate on any design, from Verilog, to SystemVerilog, to VHDL.

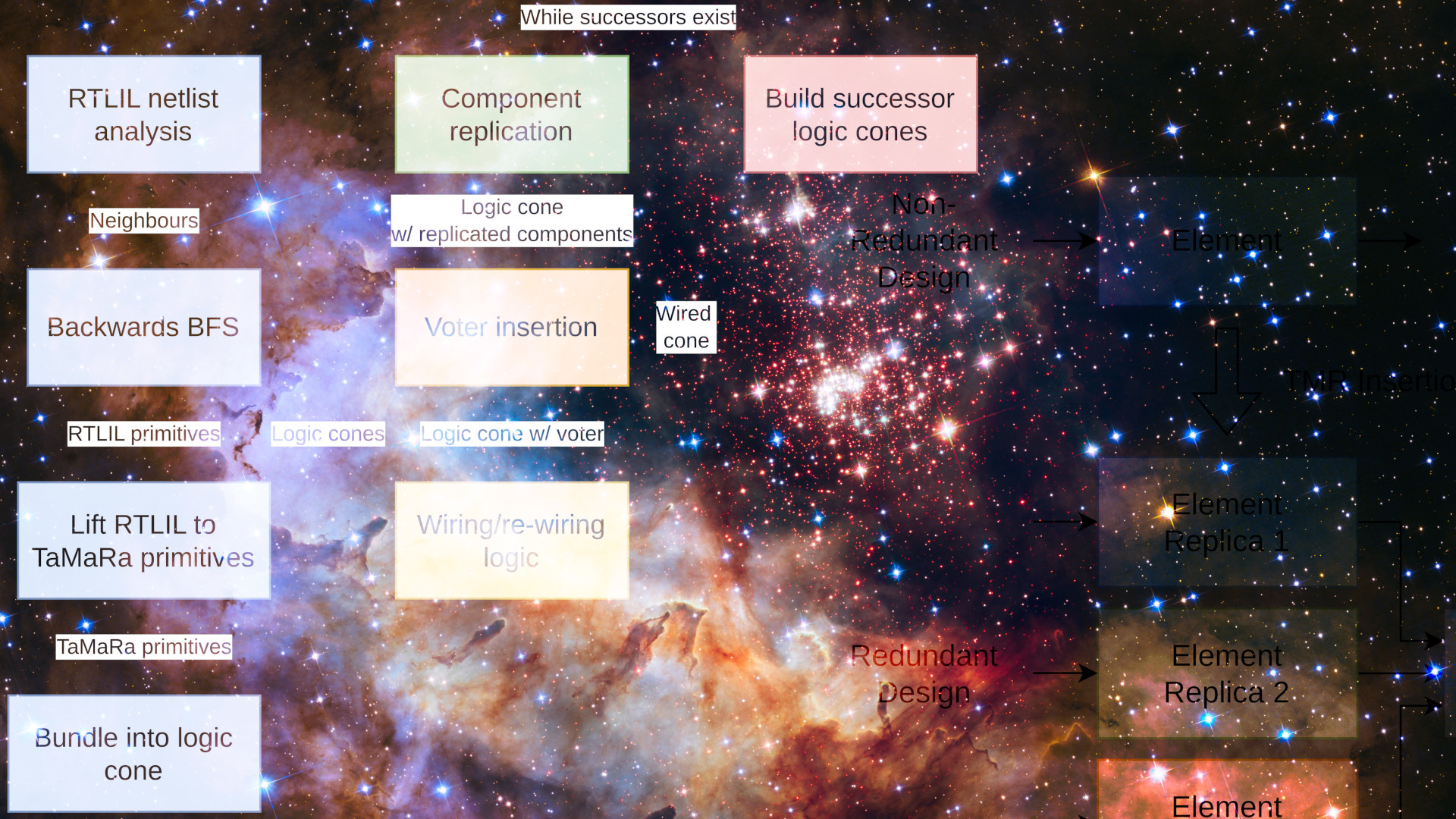

From a high-level perspective, the TaMaRa algorithm can be summarised as follows:

- Analyse the RTLIL netlist to generate

tamara::RTLILWireConnectionsmapping; which is a mapping between an RTLIL Cell or Wire and the other Cells or Wires it may be connected to - For each output port in the top module:

- Perform a backwards breadth-first search through the RTLIL netlist to form a logic cone

- Replicate all combinational RTLIL primitives inside the logic cone

- Generate and insert the necessary voter(s) for each bit

- Wire up the newly formed netlist, including connected the voters

- Perform any necessary fixes to the wiring, if required

- With the initial search complete, compute any follow on/successor logic cones from the initial terminals

- Repeat step 2 but for each successor logic cone

- Continue until no more successors remain

This is also summarised by this diagram:

From an implementation perspective, the TaMaRa plugin consists of just over 2,300 lines of C++20. The class diagram of the implementation looks (mostly) like this:

TaMaRa works by first lifting the RTLIL into a higher-level, more abstract representation: an abstract

TMRGraphNode with CellNode, IONode, WireNode and FFNode specialisations. These in turn abstractly

represent the key parts of an RTLIL circuit we care about for TMR. With this, we can more easily build a

data structure mapping between these higher-level constructs and what other higher-level constructs they

connect to. Essentially, we’re building an abstracted view of the netlist for the purposes of TMR.

One of the more important aspects is this algorithm is the concept of a backwards breadth-first search. Working backwards from the output ports of a module, towards the input ports, we look to perform a data structure known as a “logic cone” through a BFS.

Essentially, the logic cone encapsulates all of the combinatorial RTLIL primitives between a sequential primitive (i.e. a DFF) or an IO (i.e. the edge of the circuit, the inputs). This diagram helps to better illustrate a logic cone:

Once we have these logic cones, we can treat them independently to perform TMR. All of the primitives within a single logic cone can be triplicated, and a voter circuit can be inserted on the output side of the logic cone.

Insertion is no easy task - in the thesis, I refer to this as splicing or wiring and it remained one of the most complex tasks of the project. RTLIL’s power is a bit of a drawback here. As it’s capable of representing any RTL schematic at all, there are a number of edge cases to consider, and not all were able to be considered in time.

There’s a lot more nuance here than can realistically fit in a blog post, so if you’re interested, I highly encourage you to read my thesis and/or code. This goes into more detail about:

- Specifics about the backwards BFS including search termination conditions

- Specifically how splicing is done

- How the voter circuit was generated using a Karnaugh map of an expression then translated into C++ macros

- The general purpose

FixWalkerandFixWalkerManagerclasses for post-algorithm netlist repair

# Verification

For the safety critical sectors that this tool (ideally) targets, verification is extremely important. It’s

clear that the Yosys team has put a lot of effort into its verification tooling, and it shows. I was able to

use a number of Yosys tools during the thesis: SymbiYosys, eqy, mcy, Yosys’ built-in SAT solver, the mutate

command, and external SMT solvers.

I performed equivalence checking between circuits, before and after TMR, to ensure that TaMaRa does not change the underlying behaviour of the circuit. In addition, I used Herklotz’s Verismith tool to generate random Verilog RTL in large batches, over 10,000 files per run, and run the equivalence check. This enabled me to verify the integrity of the algorithm at scale.

By using Yosys’ built-in mutate command, I was also able to use the SAT-based equivalence checker to ensure

that faults were correctly mitigated. If, after injecting a fault and applying TMR, the circuit is

equivalent to its non-fault-injected counterpart, then the TMR has worked. Likewise, we can use the SAT solver

to ensure that the err signal is set high when a fault is actually injected.

This shows that formal verification is a powerful technique to use when designing EDA algorithms, not just for IC design itself. There’s certainly more work I’d like to perform in this area in future - perhaps fuzzing Yosys optimisation passes at scale to verify their correctness.

# Results

In the end, due to time constraints (and I must admit, poor project planning), TaMaRa was only able to handle simple circuits. This does include some circuits using sequential primitives, but again, only simple ones.

To have a look at what the algorithm is capable of, here is a very simple circuit displayed with Yosys’ show

command. This particular circuit uses a 2-bit bus, feeding into a simple NOT gate.

Now, after applying tamara_tmr, you can see that the NOT gate has been replicated, and the TMR voter and error

calculation logic has been inserted:

Because of the 2-bit bus, two voters are required, which is the reason this schematic has dramatically

inflated in size from the original. You’ll also be able to see the $reduce_or cell that has been inserted

to combine the individual err signals of both the voters.

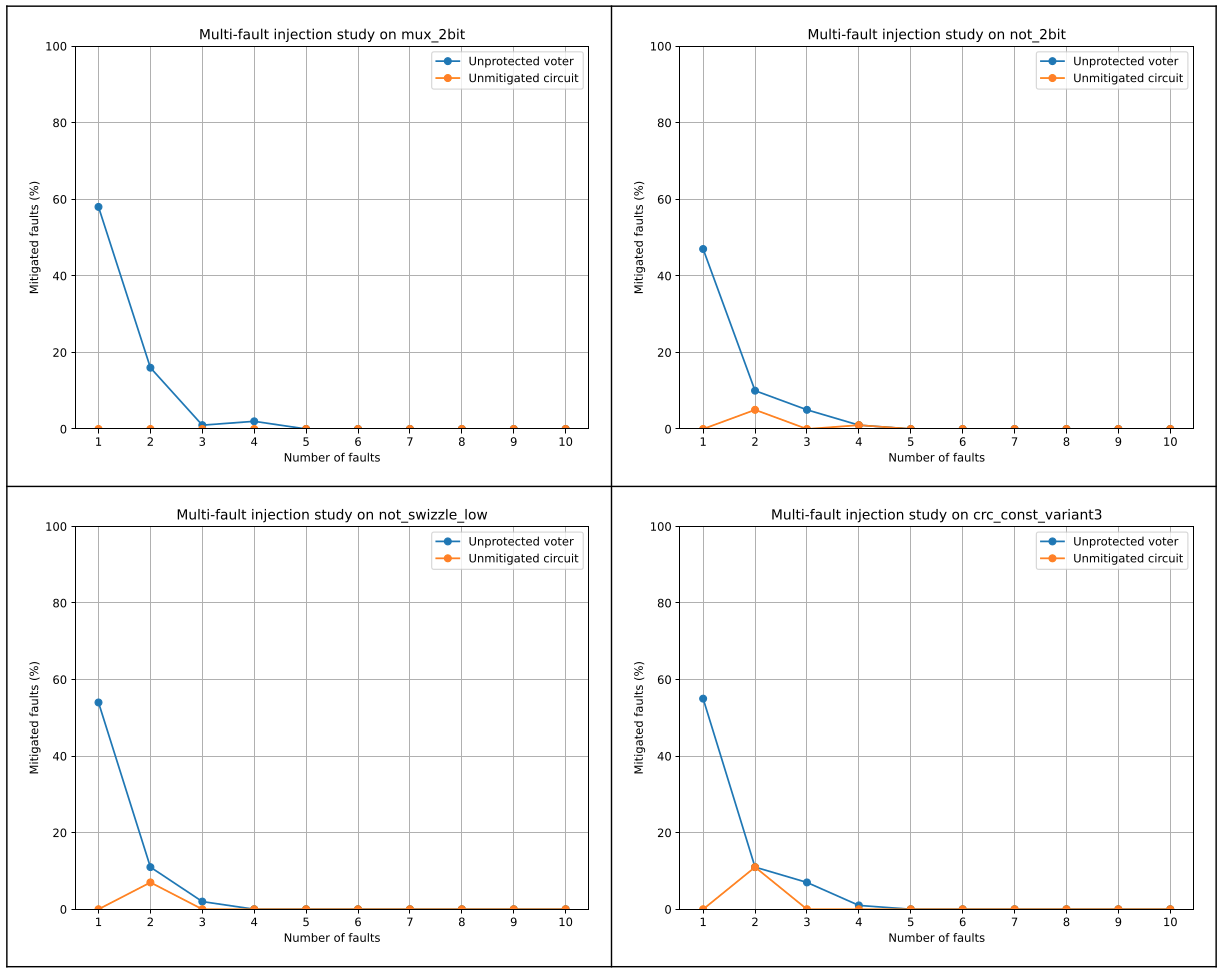

With the algorithm applied, we can also use the formal verification methodology above to analyse, at a larger scale, how these protected circuits respond to injected faults. In the following graph, an “Unmitigated circuit” refers to a pre-TMR circuit; and an “Unprotected voter” circuit refers to a circuit with a voter, subject to fault injection, where the voter may also be hit with faults as well. For each of the samples on the X axis, 100 randomised trials were used and the outputs formally verified.

This result shows that while the algorithm isn’t perfect in close-to-real-world scenarios, it does improve the reliability of the circuit somewhat. Unprotected circuits are almost always affected by simulated SEUs, whereas after being processed with TaMaRa TMR, mitigated circuits have above a 50% chance of mitigating the SEU.

All circuits tested generally perform the same, regardless of topology:

Individual circuits also appear to respond identically regardless of bit width:

# What’s next?

In 2026, I’m moving to start a PhD at Macquarie University’s Silicon Platforms Lab, one of the very few computer engineering focused research groups in Australia.

I’m planning to continue my work on domain-specific EDA, but focus more heavily on Yosys’ sister project, OpenROAD, an RTL-GDS tool for ASICs. In the case of radiation-hardening, performing this mitigation lower-down in the stack (i.e. during physical design/PnR) has the advantage of being able to more accurately consider the physical effects of radiation on the circuit. This type of information can be approximated, but is hard to accurately predict, at a synthesis pre-PnR level.

There are many fields that don’t suit typical, commercial EDA flows that focus on power, performance and area (PPA) exclusively, from radiation-hardened designs to high-security processors. Proprietary tools barricade research into this area by making them impossible to modify. Conversely, FOSS tools like Yosys and OpenROAD give us a unique opportunity, as researchers, to customise these tools to our specific areas of interest and improve the tool in the process. For example, during my PhD, I’m hoping to improve both Yosys and OpenROAD, focusing on Layout Versus Schematic (LVS) and other verification techniques. My research, and increasingly others’ as well, uses Yosys and OpenROAD for high-security and/or safety critical environments. Given this, it’s important that when we modify a tool, we know we haven’t regressed its behaviour.

My hope is that if more academics and small companies become interested in FOSS EDA tools and contribute to them, we will eventually be able to have a powerful, community-led chip design pipeline that could rival commercial tools across a number of domains. This, I believe, would make IC design an endeavour more suitable for hobbyists and academics without access to expensive proprietary tools; and unlock opportunities for interesting new innovations in the EDA sector.

# Further reading

The TaMaRa thesis (22k words) is available to read on my website, and is available under the permissive CC-BY licence.

The code is available on my GitHub, and is available under the MPL 2.0.

A reminder again that TaMaRa is absolutely not suitable for anything but simple test circuits. You are more than welcome to give it a spin, or even contribute, though!

Matt Young is a Bachelor of Computer Science (Honours) student at the University of Queensland in Australia, researching the application of novel EDA techniques to design specialised microprocessors for challenging environments.

Matt can be reached via LinkedIn or by emailing matt (at) mlyoung (dot) cool. Matt’s website has more information on TaMaRa and other projects.

Header image attributon: https://esahubble.org/images/heic1509a/ © ESA/Hubble (CC-BY 4.0)

As a special exemption to the copyright notice at the end of the page, the author (Matt Young) hereby releases this article text and diagrams under CC-BY 4.0